Important people(131)

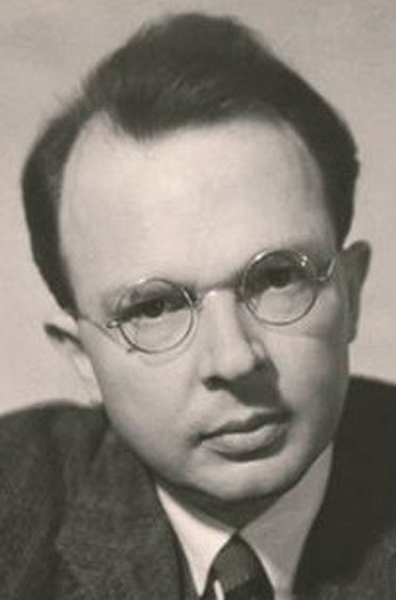

Robert Brandom(93)

An American philosopher, born in 1950.

Lectures(89)

Anti-Representationalism as Neopragmatism and Global Expressivism(29)

A lecture series taught in 2020. The course website is here.

Part 1: Antirepresentationalism as Pragmatism: Richard Rorty and Cheryl Misak(28)

Lecture 1: The Concept of Representation(9)

Representation(5)

Does ‘representation’ have a nature or a history?

Does it belong with “electrons” and “sulfur” or with “freedom” and “love”?

Brandom, being a Hegelian, thinks philosophy belongs in the latter category and proceeds to give a historical overview of ‘representation’.

History of representation(4)

Premodern theories relating appearance to reality(1)

Representation a modern concept.

Premodern theories understood relation between appearance and reality in terms of resemblance (sharing properties)

The rise of science made this untenable:

Copernicus: reality behind stationary Earth and revolving Sun is a revolving Earth and stationary Sun.

Galileo: effective strategies of understanding time as line lengths and acceleration as triangles … not easily understood in terms of shared properties.

The invention of representation(1)

Descartes invents representation with relationships between algebra (representation) and geometry (represented/reality).

Spinoza talks better about how Descartes used representation than Descartes himself. Spinoza saw Descartes’ philosophy as being understood in terms of his innovations of relating algebra to geometry.

“The order and connection of things is the same as the order and connection of ideas”

The properties of what is representing or represented are irrelevant, only that there is a mapping between the relations in each world.

If any things are known representationally, then some things must be known nonrepresentationally (to avoid infinite regress)

Representationalism gives rise to choice between epistemological skepticism vs foundationalism.

A Kantian insight: the real problem is semantic skepticism (can we really know something by representing it correctly?)

Rationalists vs empiricists(1)

Kant says Descartes was right to think in terms of representation but that he didn’t distinguish two different kinds: picture like images/sensations vs sentence-like thoughts.

He saw both as different ends of a spectrum, while empiricists tried to reduce thoughts to pictures and rationalists vice-versa.

Spinoza’s interpretation of Descartes gives another view: within a representational picture, empiricists are atomists whereas rationalists are holists

Brandom’s interpretation using orders of explanation: empiricists treat representation as a primitive and infer reason-relations in terms of it. Rationalists treat reason relations as primitive, explain representational content in terms of inferential relations.

Rationalist Leibniz would have us understand the content of the map as the inferences that someone who treats it as a map could make about terrain facts (e.g. a river) from map-facts (wavy-blue line).

Sellars identifies both camps as descriptivists (to be conceptually contentful is just to describe / represent how things are).

Empiricists start with narrow postulate about what representing is and exclude a lot of genuinely contentful thought due to not meeting this standard (e.g. ethics, modality)

Rationalists take all our cognitively contentful expressions as therefore being part of the actual world, resulting in ontological extravagance (postulating objective values/universals/propositions/laws)

Sellars saw the Tractatus as teaching us how to get beyond this ideology with the case of logical vocabulary

Representation is a wider concept than description - Brandom thinks that Sellars’ anti-descriptivism is a form of anti-representationalism.

E.g. proper names represent without being descriptions, in Naming and Necessity.

Lessons from the Enlightment treatment of representation(1)

Representation is a holistic conception, so rationalists were right about that (think: categories, relationships over properties)

Representation/description involve subjunctively robust relations between representings and representeds.

Considering the inferences of map facts to terrain facts, we also must accept that if the terrain were different, the map fact would be different.

Related to Fodor’s account of representation in terms of “one-way counterfactual dependencies of ‘horses’ on horses”.

Representation has a normative dimension

To treat representation as concerning what inferences we can make is a normative order.

Hegel appreciated this: to count as representing something is to be responsible to the represented thing (what is represented provides the normative standard for correctness of representing). What is represented has an authority over what is representing.

Representationalism(1)

Declarativism: a relatively defensible representationalist position

Dual to “descriptivism” which too narrowly construes representation as description (which is too constricted a notion of representation).

This too broadly understands what all declarative sentences do in terms of fact-stating / truth-aptness (‘representation’ becomes too expansive). Expressivism is one way of negating this (by declaring “X is good”, one is commending rather than fact stating).

Intuition: the question of truth can be raised for whatever is expressed by declarative sentences.

Geach’s 1960 embedding argument: “If X is good, then …” a hallmark of fact-stating (if we had close the door or praise god, it wouldn’t make grammatical sense)

We can embed moral statements that 1st wave expressivists said were not fact-stating.

QUESTION: are there any grammatically declarative sentences which cannot be embedded? Would a counterexample have to be a non-truth-apt, declarative sentence?

Declarative sentences that may not fit into the fact-stating mold of “the frog is on the log”:

Logical (e.g. negative/conditional facts), modal (e.g. necessity), probabilistic, semantic (what expressions mean or represent), intentional (possibly about non-existent objects like golden mountains / round squares), normative, abstract / mathematical.

Are these all types of facts? Do they represent features of the world?

Anti-representationalism(3)

Pragmatism as anti-representationalism(1)

Rorty characterizes pragmatism as fundamentally anti-representationalist (Cheryl Misak strongly disagrees and considers Rorty to be a false heir of the tradition)

Representationalism is an ideology - that the meaning of thoughts/talk should be principally understood in terms of representational relations the thinkings/sayings stand in to what they (purport to) represent.

It’s a crippling ideology that must be rejected wholesale, no hope of redemption.

It’s synonymous with modern philosophy, so that must be jettisoned too.

Two sides of Wittgenstein:

Tractatus = representationalism (but providing the model for moving beyond it w/r/t logical vocabulary)

Logical tradition from Frege/Russell, operative paradigm of formal calculi for artificial symbolic languages.

Possible world semantics best distillation of its representational approach to meaning

Investigations = anti-representationalism.

Anthropological tradition focuses on natural languages, in tradition of Dewey. Rorty claims Heidegger also in this tradition, which both sides (pragmatists and Heidegger allies) don’t like. Focus is not on meaning but on use.

Arguments:

(Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature) - representational in semantics leads to an unproductive oscillation in epistemology between skepticism and foundationalism

Pragmatism about norms

antiauthoritarianism argument (completing the emancipatory project of the Enlightenment)

Expressivism as anti-representationalism(1)

Simon Blackburn applies local expressivism in order to get a distinctive flavor of antirepresentationalism.

“Fact stating discourse” can be regarded as crucially important without dismissing all other kinds of discourse as defective/reducible.

Expressivism is a broad family of views claiming some areas of discourse are ‘in the business’ of giving expression to sentiments/commitments/non-cognitive or non-representational mental states or attitudes.

Modern anti-representationalists(1)

Huw Price synthesizes these two strands of anti-representationalism.

Agrees with Rorty that representation should never be used to do substantial explanatory work. They are global antirepresentationalists, which is a radical position currently.

He unites original German global expressivism (beginning with Herder) with second wave local expressivism of Blackburn and Gibbard.

rejects local expressivism, which requires us to distinguish vocabularies which should be given representational analyses or not - however he argues this cannot be done without embracing declarativism which the local expressivists wanted to avoid.

He reads into later Wittgenstein to unite global expressivism with Rorty

involves distinction between traditional object naturalism (how can we reduce facts in terms of natural science truth-makers) and the pragmatist’s subject naturalism (only seeks that reduction for the discursive practices consisting of use of language).

Brandom argues this global antirepresentationalism goes too far - prioritizing use over meaning (i.e. semantics answers to pragmatics) does not rule out representational/descriptivist accounts of vocabularies in general.

Disagrees with Pryce’s argument that local expressivism is not possible.

Lecture 2: Rorty’s Critique of Enlightenment Representationalism, and (so) of Analytic Philosophy(4)

Rorty's basic idea(3)

Neokantianism vs socialized/historicized/naturalized alternatives(1)

Neokantianism vs socialized/historicized/naturalized alternative.

Struggle between two camps in the 19th century, which is then re-enacted in the 20th century

Neokantianism (Marburg / Freiburg to CI Lewis and Carnap). Philosophy has sovereign authority.

Idea originates with Plato, but Descartes/Kant/representationalism are modern versions.

Neohegelianism (Hegel socialized philosophy, Marx naturalized it). Philosophy brought ‘down to Earth’.

Bertrand Russell and Husserl found things for philosophy to be apodictic about. Basis of Rorty’s ‘astonishing’ claim that analytic philosophy is just a phase of neokantianism

Russell and those downstream don’t think of themselves this way.

But they share the idea that philosophy of language is “first philosophy” and that linguistically-inflected philosophy of mind could advance our notions of epistemology and general theory of representation.

Shared emphasis on understanding language semantically, distinct from understanding knowledge epistemologically.

Husserl subject to Sellars’ critique of the Myth of the Given, Russell subject to Quine’s critique of Myth of the Museum. (Carnap subject to both).

“Uncritical semantics is the myth of a museum in which the exhibits are meanings and the words are labels. To switch languages is to change the labels”. Against the museum myth, Quine argues here for the indeterminacy of “meaning” and translation.

These are both (semantic) holist arguments.

Rorty regards the pragmatist/holist Quine+Sellars rebuttals as bringing us back to Dewey’s socialized/historicized/naturalized philosophy, with the 20th century being a pointless, big detour (despite increase in technical advances in logic/language).

Assimilation of two kinds of privileged representations(1)

Two kinds of privileged representations: sense impressions and representings of meaning (meanings thought representationally instead of functionally)

Rorty sees common genus to analytic meaning-articulating claims and the sensory given: privileged representations

common origin: role as infinite regress stoppers for the two types of representations, sensuous intuitions and inference-licensing concepts, that Kant distinguished (which each have these relations of privilege/authority).

Agrippan trilema of alternatives to skepticism

justification always in reference to other claims which require justification (this can be circular or infinite regress) OR there are unjustified justifiers / foundations.

If we have foundations, we need two kinds of regress stoppers:

premises that have authority

inferential transitions that have authority

These are not the same as premises, c.f. Tortoise and the Hare

That the “privileged representations” are authoritative and immediate, a kind of atomism follows from their privilege.

In order to play their epistemically-privileged roles, the regress stoppers must be semantically-privileged insofar as not depending on any collateral epistemic commitments.

Quine and Sellars’ critiques render such semantic privilege as practically unintelligible. A requirement that cannot be fulfilled.

Holism of Sellars and Quine(1)

Holist/pragmatic arguments of Sellars (against sense-givenness) and Quine (against meaning-givenness) that connect epistemology and semantics.

Sellars in EPM

Locke got confused by conflating the causation of a belief from its justification.

Sense data may be causally prerequisite to knowledge, but it cannot justify belief (it’s not conceptually contentful, in the sense of standing in reason relations of implication/justification).

To stand in reason relations requires lots of other infrastructure, such that atomic sense data cannot do this on its own (this is a semantic holist argument)

How do we acquire knowledge in the semantic holist POV?

How to get into the game of giving and asking for reasons? “The light dawns slowly over the whole” We need to get good enough at making the ‘right’ moves (as judged by ‘competent speakers’ before counting as a ‘competent speaker’.

Quine in TDE

Target: analytic truths, e.g. “cats are mammals” supposedly not depending on any other commitments but rather immediately from the meanings of the words.

What is the practical difference between these truths and very general facts, such as “there have been black dogs”.

Duhem-Quine thesis: “it is impossible to test a scientific hypothesis in isolation, because an empirical test of the hypothesis requires one or more background assumptions”.

What inferences we are allowed to make depends on the whole of collateral beliefs we have.

The unit of meaning must be the web-of-belief rather than the concept or the sentence.

Fodor argues against this, considers mixing epistemology and semantics to be a big philosophical mistake initiated by Quine.

Who is Rorty opposing?(1)

Is Rorty attacking a strawman? Empiricism / Epistemic foundationalism is not popular now:

“Default and challenge” structure a way of avoiding Agrippan trilemma.

Bayesianism sees all justification as comparative (never have to justify one’s prior commitments).

though the problem of semantics is still open if it is to not be representationalist

Naturalism + representationalism remains unchallenged.

picking an ontologically privileged base vocabulary

So Rorty and Pryce need to do one or both of:

Argue independently for pragmatism, then use that to attack representationalism without passing through foundationalism

Argue independently against representationalism and propose pragmatism as the best alternative approach

Lecture 3: Rorty Finds His Pragmatist Voice(15)

Major lessons(1)

(From the discussion of truth as “what is best in the way of belief” as opposed to correspondence with reality):

How the combination of:

declarativism

blurring out all distinctions of kind of claimable

expressivism

a local expressivism about what one is doing in attributing truth—namely not describing the claimable, but endorsing it—

underwriting a global antirepresentationalism because of special properties of the vocabulary of truth

together underwrite a Jamesean understanding of truth-talk.

This role for an expressivist move in a pragmatist argument forges an important link between the first and the second halves of this course.

(From the discussion of representation):

What is really at stake in the battle between a representational model of the content of expressions and a pragmatist model is the best order of explanation (a way of thinking about conceptual priority) between representational relations and reason relations (of implication and incompatibility).

Davidson teaches us that and how taking reason relations as primary (the pragmatists says, because giving and assessing reasons, implicitly and practically appealing to justificatory reason relations, specifiable in a deontic normative vocabulary of “commitment” and “entitlement”’) holistically determines representational relations in top-down explanatory stories.

Representationalists are committed to atomistic objective usually causal relations (specifiable in an alethic modal vocabulary) determine reason relations.

A. Introduction to Pragmatism(8)

Platonist Pragmatist Distinction(1)

Rorty takes for granted a distinction of Dewey:

| Platonism | pragmatism |

|---|---|

| Principles | practices |

| Theoria | phronesis |

| Knowing that | knowing how |

| End the | Continuing the conversation |

Platonists look for a principle or rule, something explicit or that could be made explicit, behind every implicit propriety of practice.

Pragmatists argue that explicit principles or theories float on a vast sea of implicit practical skills.

For example, a cobbler can make good shoes. The Platonist looks for what form is behind his mastery, what principle / mental representation makes it possible that the cobbler does that? The pragmatist treats the skill as prior to the principle.

Rorty sees representationalism as the distinctly modern form of Platonism as described above.

Kant is the avatar of this form of representationalism: representations and rules are two sides of the same coin. He puts principle over practice (opposed by Dewey, who was followed by Heidegger and Wittgenstein in this respect).

The 'vocabulary' vocabulary(1)

This is Rorty’s way of talking about language games. Or paradigms (in the Kuhnian sense - Kuhn was writing just down the hall from Rorty). Vocabularies are what we deploy in discursive practice.

He thinks is needed as a successor notion to the idea of languages and theories, which was rightfully taken apart by Quine’s Two Dogmas of Empiricism.

Examples, how big are they? - on the one hand, the vocabulary of 16th century theology - also, the vocabulary of modernity - where that’s presumably an autonomous discursive practice

Philosophers think that they are debating about what is true in a given vocabulary when really their question is better framed as trying to pick the right vocabulary (important to realize this, since it changes how we compare arguments).

This point appears to be accepting the Carnappian distinction of theory and

Rorty makes fun of representational realists as being committed to the idea that there is a thing such as “nature’s own language” / “nature’s own vocabulary”

He sees Lewis as committed to this as the language which determines what the ‘natural properties’ are.

Rorty doesn’t draw a line between speaking in a vocabulary and changing your vocabulary (he thinks almost all speech acts change it).

Duhem point: if we acknowledge that your meanings at least partially determine what inferences are good. What follows a given sentence depends on what auxiliary hypotheses you’re allowed to use as collateral premises for

We can see what else you’re committed to has an effect on that sentence, given the meaning of that sentence is characterized by its inferential relations.

In mature sciences a lot of work is taken to allow for discourse to proceed as if the vocabulary were fixed

The discursive equivalent of “clean rooms”, maintained through heroic social disciplinary measures

This is for mature sciencies: if you think of the history of temperature, every single time a new way of measuring temperature was discovered, the concept changes

But it would be a serious mistake to take this extreme, artificial case to be the paradigm on the basis of which we understand the use of language in general. (Here we might think of Heidegger on the effort it takes to precipitate Vorhandenheit out of Zuhandenheit.

Rorty says: “On the pragmatist account, a criterion (what follows from the axioms, what the needle points to, what the statute says) is a criterion because some particular social practice needs to block the road of inquiry, halt the regress of interpretations, in order to get something done. So rigorous argumentation-the practice which is made-possible by agreement on criteria, on stopping-places - is no more generally desirable than blocking the road of inquiry is generally desirable. It is something which it is convenient to have if you can get it. if the purposes you are engaged in fulfilling can be specified pretty clearly in advance (e.g., finding out how an enzyme functions, preventing violence in the streets, proving theorems), then you can get it. If they are not (as in the search for a just society, the resolution of a moral dilemma, the choice of a symbol of ultimate concern, the quest for a”postmodernist” sensibility), then you probably cannot, and you should not try for it. The philosopher will not want to beg the question between these various descriptions in advance.”

Redescription(1)

The generation of new vocabularies.

This is the essence of discursive practice, is to be committed to a view of conversation as something to be continued.

But one can do other things with vocabularies than use them to describe. So “redescription,” though evocative, might be replaced by “recharacterization,” or “reconceptualization.”

Conversation(1)

“Pragmatists follow Plato in striving for an escape from conversation to something atemporal which lies in the background of all possible conversations”

Conversation is about redescribing our vocabulary as much as using it. It is the process that produces redescriptions.

Quantifying over all possible vocabularies is a temptation and something you would only attempt to do if you are trying to end all conversation. This is a fundamental mistake. - This is something the early Wittgenstein did in the Tractatus - He then learned not to do this. It’s related to his later view that language is a motley. - Dummett interpretation of Wittgenstein: - Wittgenstein would think that if there were any use for a philosophical notion of meaning, the point of having a notion of meaning would be to codify proprieties of use. - But there is no limit of things one can use language for, so we cannot systematically find all meanings of all expressions. - Wittgentstein tool analogy: - you would think that you could describe the different ways of using things in terms of what you do with them in the way you could tools, so that you could think of hammer and nails, screw and screwdriver, glue and glue brush, all his ways of attaching things to one another. And that would be a sort of common function that they could perform - Early W. thought ‘Yes, representation is like that. That’s what language is for’ - What about a wrench What about the pencil that the carpenter uses, or the level that the carpenter uses, or the tool belt or tool chest? Or the set of plans that they’re using? - All these are functioning differently, and there isn’t going to be a systematic way of saying all the different kinds of tools that you could have - Classic Wittgensteinian anecdotes turn on the malleability of language. (tooth example) - The metaphyiscal puzzle comes from having a STATIC, totalizing pictures of language rather than accepting it as a motley that evolves whenever you use it. - We carefully design mature natural science and math to not have this happen, but this should not be a model for how our language works. - This is why Wittgenstein is a semantic nihilist, he doesn’t think there are actually meanings. The plasticisty of language makes this impossible.

Linked by

Coping(1)

Rorty has another term that is part of the constellation that starts with “vocabulary” and includes “redescription” and “conversation.” It is “coping.” It is his generic term for what we do with vocabularies, generally. It is in terms of success at coping that we are able sometimes to assess and compare vocabularies as better and worse. In that regard, it plays a role analogous to the notion of accuracy of representation, that Rorty wants to persuade us to discard as specifying the dimension along which arbitrary vocabularies can be assessed as better or worse.

It is crucial to this notion of coping that standards for it are rigorously internal to the vocabularies being assessed.

Different kinds of facts are identified individuated by the vocabularies we use to state them. (e.g. Physical Facts, normative facts, nautical facts,…)

Rorty concludes if it doesn’t make sense to quantify over all possible vocabularies, then it doesn’t make sense to quantify over all possible facts (a new vocabulary is going to make it possible to state new facts)

B. Radical Bifurcationism(1)

Rorty rejects the distinction of objective and subjective facts.

(Stopped taking notes at 1:11, pg 6 of Brandom’s presentation notes)

old(5)

Empirical vs other vocabularies(1)

Is there a bifurcation in ordinary empirical description vocabulary vs vocabularies where there isn’t a good correspondence between parts of the sentence and parts of the world? -E.g. “Jupiter has moons” vs “The universe is infinite” and “Love is the only law”

Representationalists can either 1.) postulate objects represented by the latter claims (e.g. love) or 2.) consider such sentences that don’t fit the representational mould as defective/inferior.

These latter claims definitely have a meaning though, as observable by the reason relations they stand in.

Brandom claims that the representationalism-vs.-antirepresentationalism issue is distinct from the realism vs antirealism one, because the latter issue arises only for representationalists.

Coping(1)

Is “coping” talk just an evolutionary biology / memetic thing?

This ‘reductionist’ interpretation is not true for Rorty:

Language is not a tool, as Dewey would have it, though it’s a nice metaphor for some purposes, it can be stretched too far:

Tool requires a common purpose that you can compare different tools for (e.g. nails / glue / screws all are tools for sticking wood blocks together)

But we cannot formulate the goal of language without already having language (we don’t have access to “nature’s true language” to do this, either).

Thus the meaning coping must be within to some vocabulary.

On meaning(1)

Brandom summarizing Wittgenstein: ‘Meaning’ is a theoretical object-kind, postulated to codify proprieties of practice

it is no truer that: - “atoms are what they are because we use ‘atom’ as we do” - than that “we use ‘atom’ as we do because atoms are as they are.” - Both of these claims, the antirepresentationlist says, are entirely empty. - Both are pseudo-explanations. - It is particularly important that the antirepresentationalist insist that the latter claim is a pseudo-explanation.

Davidson lesson(1)

The most general lesson of the discussion of Davidson is that the overall collision is between

the intrinsically holistic demands of reason-relations, understood in interpretivist terms by Davidson, and (also) in social-practical terms by Rorty,

Interpretism: to say someone is a believer is to invoke the possibility of interpreting their beliefs and actions together (in a way that maps onto our own beliefs)

While having a conversation with someone is how you learn what they mean by X, the fact you can have a conversation is what it means for them to mean something by X.

To say that someone believes something is to claim we can have a conversation with them.

and the claims representational relations determined independently of social practices of giving and assessing reasons, for instance (and paradigmatically) by objective, causal relations describable in alethic modal terms

Davidson is happy to impute extensions (referents) as an intermediate stage of interpretation. But he insists that the process be top-down, starting from reason-relations to assignments of referents.

Davidson’s big contribution:

flipping Tarski’s theory of truth:

Tarski: if you take meanings fixed, I can give you a recursive theory of which statements are truth.

Flipped: You can take ‘meanings’ to be the truth conditions (of all of the language). The starting point is the reason relations, and from those we derive the meanings.

We can argue about which order of explanation is better. Bottom up vs top down.

Bad theories

E.g. witches, phlogiston

We often find ourselves saying “Hard to say whether they’re talking about real things but are wrong about most of them or not talking about real things”

To what degree do ‘witch’ and ‘phlogiston’ refer?

It’s a matter of degree and a pragmatic decision.

So any theory that has as a consequence that there is a precise line between reference or non-reference is wrong.

On Sellars(60)

Robert Brandom taught a recorded graduate seminar on Wilfred Sellars twice, in 2009 and and 2019. Notes on the recordings of these lectures are collected here.

Lectures 2009(44)

Lecture: Historical context and quotes(7)

The first of many lectures by Robert Brandom on Wilfred Sellars, delivered on September 2, 2009. It mainly talks about some ideas of Kant that influenced Sellars and introduces Sellars through a long series of quotes.

Historical Kant Context(5)

Kant was not in favor within analytic philosophy when Sellars began, due to Kant’s connection to Hegel2. However, this is ironic because Kant is incredibly analytical and science-driven.

Three ideas of Kant that mattered to Sellars:

Kant's normative turn(1)

Kant’s normative understanding of discursive practice3

How do we understand the difference between concept-using, sapient beings from mere responders to the natural environment? Here are two possible ways to think of it:

\(O\): An ontological distintion: knowers are an actually different kind of thing (perhaps there is a presence of ‘mind stuff’ or ‘spirit stuff’).

\(D\): A deontological distinction: we treat knowers differently from objects. There are things that the agents are in a distinctive sense responsible for 4.

Both sides treat \(D\) as true, but Team \(O\) furthermore believes \(O\) is true and that the order of explanation is \(O \implies D\). However, Team \(D\) takes \(D\) as essential and needs not make any claim about ontology.

Downstream of this are many of Kant’s innovations.

The minimum unit of awareness/experience is the judgment

this comes from taking \(D\) to be fundmental: it is the smallest thing we can be held responsible for

Everything else (particular concepts like Fido the dog, universal concepts like triangularity, logical concepts) has to be understood in terms of the function it plays with respect to judgment.

The subjective form of judgment (the “I think…” that can accompany all judgments)

Because it can accompany all representations, this is the emptiest form of judgment.

The mark of “who is responsible for the judgment”.

To say “I think it is raining now.” is to emphasize that I am responsible (e.g. subject to criticism if you go outside and don’t get wet).

The objective form of judgment (the “\(x\) is …” or “\(x\) = …” for some object \(x\)).

Mark of what you’ve made yourself responsible to.

When saying “That stone is 50 pounds.”, the stone has a certain authority over me (one looks to the stone to see whether I am right or wrong; it sets the standards of correctness). See the shopping list scenario.

Linked by

Turning Rousseau's definition of freedom into demarcating the normative(1)

Rousseau said “Obedience to a law that one has laid oneself is freedom.”

Kant turned this around to distinguish constraint by norms from constraint by power.

Pure concepts of the understanding(1)

In addition to concepts whose principle expressive job is to describe/explain empirical goings-on, there are concepts whose principle expressive job it is to make explicit the framework that makes description possible.

These are known a priori framework-explicating concepts.

This is Kant’s response to Hume, for how we can understand the modal force of laws in virtue of their non-modal description.

The answer is in the description framework itself.

The fact that there are necessarily relations that concepts have among another makes description possible (a concept being contentful at all requires it to have some necessary relations to other concepts).

What Sellars means by ‘ushering philosphy from its Humean phase to its Kantian phase’ is putting categories front and center.

Trying to describe the modal structure of the world or describe the space of possible worlds is to try to assimilate modal language into descriptivism, rather than seeing them as playing a different expressive role

Sellars saw Kant as putting this other option on the table.

A difference between Humean thinking and Kantian thinking: for Kant, laws of nature are not ‘super-facts’ - they are not ‘describing the world’. Rather, they make explicit a rule of inference.

Another Kantian idea: the distinction between phenomena and noumena:

Kant radicalized the distinction between:

primary qualities (properties that are truly there)

secondary qualities (properties that are due to us).

He challenges us to divide the labor:

what features is the world responsible for?

what features are we responsible for?

E.g. the fact our theories are expressed in German/English

This distinction lives in Sellars as the difference between:

the world in the narrow sense

the world in the wider sense

E.g. which includes norms that are only accessible from a participant’s perspective.

The lecture finishes with some Sellars quotes on describing, explaining, and justifying.

He doesn’t begin with philosophically elaborated definition of describing, explaining, justifying. He takes these concepts as they come. He wants to do philosophy in a neutral / as close-to-practice way as possible.

Lecture: Inference and Meaning and Language Games(9)

This lecture was delivered on September 9, 2009. It coverse [3] and [11].

Sellars Style(1)

‘Mystery story’ style:

There’s a problem, and many competing potential explanations

These explanations engage each other dialectically

Only at the end would you learn the philosopher’s actual position

‘Journalistic’ style:

Tell them what you’re going to tell them

Tell them

Tell them what you told them

Sellars philosophical style is more the former.

Material inferences(1)

Let an inference be a declaration of the form \(P \implies Q\)

There, \(P\) and \(Q\) are logical variables. We can also put other things in their place:

Non-logical vocabulary, e.g. red, cat, or it’s raining outside

Logical connectives: and, or, etc.

We want to distinguish certain inferences as material inferences, as distinct from logically-valid inferences.

Logically-valid inferences:

These are inferences that are true no matter what you plug in for the variables or substitute for the non-logical vocabulary.

E.g. \((A \land {\rm it's\ raining}) \lor C \implies (C \lor {\rm it's\ raining})\)

This is true, regardless of what we substitute for \(A\) and \(C\) (or swap “it’s raining” for anything, e.g. “I own two cats”).

Descriptive terms appear vacuously

Material inferences:

These can be changed from a good material inference into a bad one by substituting some nonlogical vocabulary for different nonlogical vocabulary

E.g. the material inference “\(a\) is red” \(\implies\) “\(a\) is colored” will become false if we replace ‘colored’ with ‘square’.

Descriptive terms appear essentially

Linked by

Sellars' main ideas on material inference(1)

Sellars has two good ideas associated with material inference:

There are some inferences that are good, not in virtue of their logical form.

Turn the above thought on its head and say: we can understand the content of these descriptive terms in terms of the materially good inferences they appear in (as premises or conclusions).

By this account, material proprieties of inference are more fundamental than / conceptually prior to logical validity. You have to start with the notion of a good inference in order to understand what a logically good inference is.

Linked by

Aside about the Philosophy of Logic(1)

Aside: It took a while in the 20th century to realize that logic was not about logical truth but rather about validity of inference. In classical logic can you treat these interchangably, but not all (rough logics vs smooth logics - whether the consequence relation can be determined by the set of all theorems). Dummett has written about this issue.

What if we picked some other vocabulary (other than logical) to hold fixed? E.g. substituting non-theological vocabulary for non-theological vocabulary. “If justice is loved by the gods then justice is pious”. If no matter what we substitute for justice the inference is good, we might say the sentence is true in virtue of its theological form.

Philosophy of logic (See Quine’s and Putnam’s books both titled The Philosophy of Logic) has two classic questions:

a demarcation question: what makes something logical vocabulary?

Quine disallows second order quantifiers and the epilson of set theory, whereas Putnam allows them.

a correctness question: which logical consequence relation to use:

Classical? Intuitionistic? etc.

Sellars challenges this tradition (logical empiricism) by pointing out there is a concern conceptually prior in the order of explanation to philosophy of logic: materially good inferences.

Inference and Meaning(3)

A main argument of Inference and Meaning is that any language that makes essential use of non-logical, descriptive vocabulary must be understood as having that vocabulary standing in materially good (rather than just logically good) inferences.

A slogan for this: “Concepts as involving laws (and inconceivable without them)”

This is actually the title of an unintelligible essay by Sellars

Luckily the title is the thesis, and that much is intelligible

Sellars claims logical vocabulary has the expressive job of making explicit the material proprieties of inference that articulate the content of non-logical concepts.

More specifically than ‘logical’, he means alethic modal vocabulary: i.e. what’s necessary and what’s possible.

Historical note: Frege is more explicit about this point than Sellars: that you can use this to distinguish logical vocabulary.

The Montaigne example) highlights the difference between the capacity to use material inferences vs making that inference explicit:

Dan Dennett argues that we have to take animals as grasping modus ponens because they treat some inferences as good and others as bad

Sellars objects, saying that you could make explicit the practical capacity the animal has via a statement of disjunctive syllogism

But what is the surplus value of invoking that explicit expression? (Over simply describing what is the dog can do).

Talking about following rules very quickly gets into the regress of rules.

There have to be some practical moves you’re just allowed to make without them having to take the form of explicit premises (see Tortoise and Achilles).

Sellars touches upon this in Reflections on Language Games.

He talks about free/auxillary positions that you’re always allowed to occupy.

We could have the auxillary position \(\forall x, \psi(x)\vdash \phi(x)\) which would license us to move from a position \(\psi(a)\) to a position \(\phi(a)\), but we could also encode this with position for each possible move (\(\psi(a)\vdash \phi(a)\), \(\psi(b)\vdash\phi(b)\), ...).

He ways that we could imagine replacing positions with moves, but it’s not possible to imagine all moves being replaced with positions (‘a game without moves is Hamlet without the Prince of Denmark’).

Sellars is addressing tradition that wants some small set of explicit principles in accordance with which to reason. Any inference you think is good that isn’t derivable from that small set of principles (e.g. modus ponens) is actually an infamy (has some suppressed premises). This is early analytic philosophy’s embrace of the new logic. Sellar’s contrary view (radical at the time) is that actually the reasoning could be completely in order, just with material proprieties of reasoning. You can still give/ask for reasons and mean that \(p\), but what the logic does is give you meta-linguistic control to talk about what is a good inference and say that \(p \vdash q\) is a good inference.5

Example: \(A\vdash B\) where \(A\) is “she asked me to hand her the dish towel" and \(B\) is “I shall hand her the dish towel”. Traditional analytic philosophy will call this an infamy, since it does not explicitly state how her request engages my motivational structure. Sellars would want to say that this invocation of the desire makes explicit the endorsement of \(A \vdash B\) rather than referring to some item of the world.

Brandom: logic is the organ of semantic self-consciousness. The set of concepts that lets us bring our endorsement of some inferences as good/bad (this endorsement as something that reasons can be given or asked for) into the game of giving/asking for reasons.

Sellars complains about Carnap treating logical consequence as a syntactically definable relation between sentences. Just writing down the rules under a heading ‘rules’ instead of ‘axioms’ isn’t making explicit the normative force they have (it leaves out the rulishness - that a rule is a rule for doing something). This is a subtle point that doesn’t matter for many purposes, but Sellars believes it’s important if you want to understand what’s going on with reasoning. Again, strong connection between this point and Achilles and the Tortoise.

“There’s an important difference between logical / modal / normative predicates on the one hand, and such predicates as ‘red’ on the other.” There’s nothing to the formal except their role in reasoning, indeed, their role and make as meta linguistics sort of making explicit something about the ground level. For the latter, he wants to argue that these predicates too are meaningful insofar as their role in reasoning, but it’s less obvious.

“Red is a quality”. This conveys the same information as the syntactical sentence “Red is a one place predicate.” See quote. What you’re doing in asserting that premise from which to reason (couched in modal vocabulary) is endorsing a principle in accordance with which to reason (couched in normative vocabulary).

We cannot completely identify modal and normative statements with each other. Their relation is characterized by the say/convey distinction.

Say/Convey distinction(1)

When I say "copper melts at 1084 degrees" one makes a claim that is true even if there were no reasoners (so it can’t be a claim directly about inferences being good). What it conveys is about inferences, not what it says. Likewise, I say “The sun is shining” while I convey “I believe the sun is shining.”

It might help to make progress toward understanding the say/convey distinction (which Sellars admits he’s not clear about) by distinguishing two flavors of inference:

semantic inference: good in virtue of the contents of the premises and the conclusion

pragmatic inference: good in virtue of what you’re doing in asserting the premises or the conclusion.

e.g. John says ‘your book is terrible’ and I infer that he’s mad at me

Geech embedding distinction between the two: we look at whether we’d endorse “My book is terrible, then John is mad at me". Because we wouldn’t, we know the inference is pragmatic.

Linked by

Do subjunctive conditionals describe possible worlds(1)

Potential counterargument against Sellars: subjunctive conditionals are not making explicit proprieties of inference, but in fact are descriptions about possible worlds. To address this, we note there are separate issues. Firstly, there’s the question about whether it’s intelligible to have descriptive vocabulary in play in a context where there’s no counterfactual reasoning. E.g. Hume believes he understands empirical facts perfectly well (the cat is on the mat) but not statements about what’s possible and necessary. But Kant saw that this isn’t intelligble - you need to make a distinction about what’s possible with the cat and what’s not (it’s possible for the cat to not be on the mat, but not possible for it to be larger than the sun) or else there’s nothing you could say about the conctent of the concept of ‘cat’ that I’ve got (it would be just a label). The second issue is the codifiability of proprieties of material inference by logical vocabulary: whether a possible worlds analysis is incompatible with seeing subjunctive conditionals as making properties of inference explicit. Sellars would like to see a possible worlds analysis that matches up.

Some Reflections on Language Games(1)

WARNING: Jotted down hastily, not yet cleaned up or fit for consumption.

Regulism (conceptual norms as a matter of explicit rules) vs regularism (norms in terms of actual regularities). These are identified with empiricist and rationalist approaches. (Kris: I also see prescriptivism and descriptivism in linguistics)

One purpose: “I shall have a chief my present purpose if I’ve made plausible the idea that an organism might come to play a language game, that is to move from position to position, the system of moves and positions, and to do it because of the system without having to obey rules, and hence without having to be playing a meta language game.” (Section 18)

He doesn’t explicitly mention Wittgenstein (who is a pariah in philosophy). (Other times he uses astrices to censor his name). Thinking about language in terms of rules is Kantian. His notion of norms was juridical/jurisprudential. A rule that enjoins the doing of an action A is a sentence in some language, which requires more rules to interpret (regress - how do we deal with it?). Kant identified this regress (A132/B171) - “judgment is a peculiar talent that can be practiced only and not taught”. Which is using distinction between things that can be shown (by examples) vs taught. Wittgenstein addresses this regress in the late 100’s of PI.

Rejecting mere conformity: If we just consider conforming to a rule rather than obeying a rule, there’s no regress, but we lose the normativity.

“[Mere conformity people] claim that it’s raining therefore the streets will be wet (when it isn’t an infamatic abridgement of a formally valid argument) is merely the manifestation of a tendency to expect to see the wet streets when one finds it’s raining. In this latter case, it’s a manifestation of a process which at best can only simulate inference, since it’s a habitual transition, and as such not governed by a principle or rule by reference to which can be characterized as valid or invalid. That Hume dignified the activation of an association with the phrase ‘causal inference’ is about a minor flaw, they continue, in an otherwise brilliant analysis. It should, however, be immediately pointed out that before one has a right to say that what Hume calls ‘causal inference’ really is an inference at all, but merely a habitual transition from one thought to another. And contrast that with in this context, the genuine logical inferences which are, one must pay the price of showing just how logical inference is something more than a mere habitual transition empiricists in the human tradition have rarely paid this price, a fact which is proved most unfortunate for the following reason. An examination of the history of the subject shows that those who have held that causal inference only simulates inference proper have been led to do so as a result of the conviction that if it were a genuine inference, the laws of nature, things that govern this would be discovered to us by pure reason. As they’re thinking of what’s a good inference having to be something that’s transparent merely by introspection in the way that the laws of logic are.” (him making point about distinction of real inferences and mere associations. )

No distinction between correct and incorrect can be made by purely pointing to regularity - as Wittgenstein pointed out, you’ll always find some regularity (there’s some elegant rule that generates the sequence, for any arbitrary sequence). This is also called ‘disjunctiv-itis’ or ‘gerrymandering objections’. After a debate between Dretsky and Fodor: we’re trying to see what makes the word porcupine mean porcupine. When ‘porcupine’ is used in an observational way, it’s typically in response to porcupines. So can we use that regularity to understand what ‘porcupine’ means? No, because of counterfactuals. If it happened that the porcupines we saw were almost always male, would the word mean male porcupine? Or if we look at dispositions, if they’re disposed to also call echidnas porcupines (that’s the disjunction), why not say that ‘porcupine’ means porcupine or echidna?

“what’s denied is the playing a game logically involves obedience to the rules of the game. And hence the ability to use the language to play the language game in which the rules are formulated.” (page 29) Need a sense of playing the game stronger than conforming but weaker than having the rules in mind.

Metaphysicus suggests why not a non-linguistic awareness of the rules? This is its own regress.

“We’ve tacitly accepted so far and the dialectic dichotomy between merely conforming to the rules and obey. But surely this is a false dichotomy. Is there something in between, for it required us to suppose that the only way in which a complex system of activity can be involved in the explanation of the occurrence of a particular act is by the agent explicitly envisaging the system and intending its realization. And that’s as much as to say that unless the agent conceives of the system, the conformity of his behavior to the system must be accidental. ” So what’s needed he’s saying, is going to be something that says, look, there’s an explanation of why he conforms to the rules. That invokes the rules, but it doesn’t invoke them by him being aware of them. One example of this is teleosemantics. See bee waggles.

The essential thing for Kant was a distinction between what was between acting according to a rule and acting according to a conception of a rule, or a representation (Vorstellung) of a rule. So, ordinary natural objects act according to rules, the laws of nature, but we act according to representations of rules / to conceptions of rules.

The explanation as to why I use the word ‘purple’ for purple things, the rule plays a crucial part even if it is not in my head. It is in the teachers’ heads (they’re already in the language and can conceive of rules). So the rule is causally antecedent to my behavior, so I can be following the rule (without regress).

Related quesiton addressed here: Classical Behaviorism

How is it that I can apply a concept according to norms, to invoke a pre-linguistic awareness of universals, that’s going to be a given. And the key thing is, because that pre-linguistic awareness is conceived of as providing reasons for me to do this. It’s not just that I’ve been trained to respond to some physiological thing by doing it (that would be okay. That could be part of the the real explanation, the pattern governed explanation). It’s that that pre-linguistic awareness provides reasons. And the claim is reasons are always making a move in a game that’s making the inferential move. And the question is: what determines the norms that govern that? Then we’re off on the on the regress, again, so we’ve got to have some story that doesn’t have that form. The form of the argument against the myth of the given. It’s the idea that the awareness that givenness provides something that can serve as a reason, but is itself not dependent on our having learned a language, having a conceptual scheme, and so on.

To do: understand language entry transitions and language exit transitions.

There is debate (but it should be more of a bigger deal, in Brandom’s opinion) about what are the minimal features needed for one to have a discursive language practice. Brandom views logical language as optional (though the expressive power would be incredibly stunted, you could still give and ask for reasons). MacDowell and Sellars think otherwise, that there can’t be discourse without a meta-language.

Sellars needs the notion of language to be something that evolves over time (rather than an instantaneous collection of rules) because we want the decision to make a material move to occur with in a language (one is not doing redescription in another language).

Lecture: Language as thought and different species of ought(7)

This lecture was delivered on September 16, 2009.

Language as thought and communication(1)

WARNING: Jotted down hastily, not yet cleaned up or fit for consumption.

Sellars wants to give us a naturalistic account of intentionality.

Logical behaviorism / philosophical behaviorism Def: the view that one can analyze without remainder intentional vocabulary / intentional concepts into purely behavior characterizations / dispositions to publicly observable behavior (specified in a non-intentional vocabulary).

Introduced in Empiricism in the Philosophy of Mind (9 years earlier), distinct from what he here calls logical behaviorism. Logical behaviorism refers to a view he attributes to Ryle. JB Watson and BF Skinner promoted this in psychology. Sellars never endorsed this because he saw this as being an application of instrumentalism in the philosophy of science.

Observable things, at least we know they exist. Theoretical things, we’ve got to make risky inferences to get to them. But we can also make observational mistakes. Not just “I thought it was a fox but it was a dog", but categorical observational mistakes. We can give some concept an observational role (e.g. declare that we can observe X’s) yet no X’s exist, i.e. no thing has such no thing with such circumstances of application and consequences of application. E.g. we can have a theory of acids. "Anything that’s sour is an acid. And anything that’s an acid will turn litmus paper red." Well, then we have observational access to acids. If we eventually find something that tastes sour that turns litmus paper blue, then it turns out there are no acids, even though we could observe them (or: had every reason to believe we could). Likewise: being a witch was observable (even though there are no such things).

The Plasticity of Mind is about bad theories incorporating observational practices, i.e. "What do you mean there are no K’s. I can see K’s, there’s one right there!"

So again, this is a response to someone saying we can distinguish theoretical from observable entities by pointing to the fact that we can make mistakes about whole categories of theoretical entities.

Just because our evidence for attributing mental states comes from behavior does not mean, unless you are an instrumentalist, that you have to be able to define intentional concepts in terms of behavior. (This doesn’t mean that the intentional states are less real, just that we aren’t in a position to observe anything but the behavior)

Digressions

Semantics is a field with instrumentalist vs theoretical realist views. Michael Dummett is instrumentalist by observing the fact that meaning something is only understood through verbal behavior and concluding that any theory of meaning must be definable in terms of behavior. (A theoretical realist might postulate meanings as theoretical entities to explain verbal behavior and say our access to meanings is inferential and, if they are good theories, then verbal behavior gives us inferential access to something (meanings) that exist.)

MacDowell and Sellars agree (and disagree with almost all others) that what you hear when someone talks to you is the words themselves, rather than hearing noises and (by some inferential process) constructing the words. You have to actually actively do some work to hear that mere noises. This is evidenced by how difficult it was to tell computers how to recognize a smile in a picture. (Some say it’s a contradiction to say that meanings are essentially normative yet, on the other hand, we sometimes can directly perceive them. But there’s nothing in principle unobservable about normative states of affairs - see Sellars’ criteria of observation below)

(Controversial) Criteria for observation:

You have the capacity to reliably and differentially respond to some normative state of affairs

You have to have the concept and which is a matter of inferential articulation and practical mastery of inferential proprieties, involving it. And then if you can hook the one up to the other, you’ve turned what was beforehand a theoretical concept for you into into the concept of an observable

Sellars wants to make sense of the notion of “language as a rule-governed enterprise" (as essentially involving norms). Sellars believes that if your account language doesn’t involven norms, you will be describing the vehicles by which we communicate, rather than what we’re saying/meaning.

Reminder that, due to the regress argument, that we need to broaden our notion of ‘rule’ from just explicit rules and need think of rules also as implicit in what we do. Sellars wants to better understand the relationship between implicit practical abilities and explicit representations of rules.

The question of whether meaning is a normative concept was brought to philosophical attention by Kripkenstein [12]. In present literature, Hattiangadi and Katherin Glüer have pushed back upon the idea that it is a normative concept, advanced by Brandom and MacDowell. Brandom feels it is because they haven’t learned lessons from Sellars, in particular thinking of norms purely in terms of explicit presecriptions and not making the distinction between ought-to-be’s and ought-to-do’s.

“You can define possibility in terms of not and necessity. You can define necessity in terms of not and possibility. I think it’s the beginning of wisdom to think of defining not in terms of the relationship between possibility and necessity, but I’m the only human being who thinks that."

Grice on non-natural meaning: reduces what a linguistic expression \(P\) means in terms of the meanings of thoughts and beliefs of those uttering \(P\). Sellars isn’t satisfied with this: the puzzling phenomena of meaning are common to both thought and language.

Sellars says “ought-to-be’s imply ought-to-do’s" but is not exact about what quantifier: all or some? Brandom thinks ‘some’ makes more sense, since there could be an ought-to-be requiring a state of affairs to change without telling us who has to do what to fix it (you need auxillary hypotheses to turn it into an ought-to-do). E.g. “all clocks should be in sync”.

With a trainer, someone with concepts/rules can condition language learners to shape their behavior (teach them ought-to-be’s). It’s important that it’s possible for the language enterprise get off the ground (i.e. without trainers). It’s possible for some sort of selection process to naturally reinforce ought-to-be’s (can be social but the conditioners need not be doing so intentionally).

We can deliberate making a distinction between ought-to-be’s in the context of humans vs nonliving/nonsentient beings (e.g. “plants ought to get enough water”). Ruth Millikan’s work relevant. Connects to the Aristotelian account.

Consider ought to be’s in the context of training animals: These rats ought to be in state \(\phi\) whenever \(\psi\).

Could be just for rats, qua rats

they ought to be eating when they’re hungry, or something like that

this could be something we want the rats to do

when they come to a branch in a maze, the rats go to the side that’s painted blue and not to the side that’s painted red.

That’s a regularity that ought to be not because we can read it off of the fundamental teleology of rats

The conformity of the rats in question to this rule does not require that they have a concept \(C\), e.g. of colors blue and red. We just require them to respond properly certain to differences emanating from \(C\). This doesn’t require even consciousness (photocells can respond differentially to colors).

“Recognitional capacity” gets systematically used in two fundamentally different senses (an ‘accordion word’)

reliable, differential response

applying a concept

Important for Sellars that following an ought-to-be requires only the former sense.

We should talk about learning a language as ‘coming into the language’ rather than ‘learning a language’. It’s more like the way one comes into a city. You come to be able to take part in an ongoing practice, as opposed to getting some intellectual insight.

Teaching the very young child to say ‘purple’ when showing her a purple lolipop is getting her to follow an ought-to-be just like the rat example. There is an ought-to-do for teachers of a language that they see to it that children produce the appropriate responses. This presupposes that the teachers do have a conceptual framework of ‘purple’ and of ‘vocalize‘ and what it is for an action to be called by a circumstance. The learner is not required to have any of these concepts. The ought-to-be is explicit in the teacher’s mind.

Instrumentalism(1)

All of our evidence in science comes from empirical observation, so all of our concepts (and claims) must be translatable without remainder into observational vocabulary.

What warrant would there be for any conceptual excess beyond the language of our evidence?

There aren’t really any theoretical entities. We postulate them merely to characterize regularities of observable entities. Statements in the observational language are simply true or false, whereas statements in theoretical language are merely more or less useful.

This is a view that members of the Vienna Circle flirted with. A permanent temptation of the empiricist tradition.

The alternative is called theoretical realism. Sellars says this is a mistake (an example of "nothing-but-ism", along with emotivism in ethics), originating from thinking of the difference between observational vocabulary and theoretical vocabulary as an ontological difference in the objects referred to by those theories. But it’s not an ontological distinction, it’s a methodological distinction. Two different epistemic relations we can stand in to things that there are. Observable things are those that we come to know about by observation (non-inferential observation reports). Theoretical concepts are concepts that we can only be entitled to apply as a result of a process of inference. See Pluto example.

Linked by

Ought to be and ought to do(1)

| Ought to do’s | Ought to be’s |

|---|---|

| Rule of action | Rule of reflection |

| If you’re in circumstances \(C\), do \(A\) | Pattern based judgment |

| Conceptually articulated | Not necessarily conceptually articulated |

| Rules of deliberation | Rule of assessment/criticism |

| First personal | Third personal judgment of some behavior |

| What’s appropriate for me to do? | Given what you did, was it appropriate? |

| The person subject to the rule is the one following the rule | There may be no particular agent at all |

| Examples? |

|

A distinction fundamental for both ‘must’ in the alethic and doxastic modal senses.

Sellars: You can’t understand either of these kinds of oughts without understanding both. In particular, if you try to do everything with ought-to-do’s:

one would fall into a kind of Cartesianism: we’d need to think of linguistic episodes as essentially the sort of thing brought about by an agent whose conceptualizing is not linguistic.

We’d be precluded from explaining what it means to have concepts in terms of the rules of the language. Ought to do’s have the form of “in circumstances \(C\), do \(A\)” - what language are \(C\) and \(A\) stated in? Regress of rules without ought-to-be’s.

This is important because natural way to think of rules is exlusively in terms of Ought to Do (Sellars himself advocated this earlier: “A rule is always a rule for doing something"[3]).

There is also an analogous distinction involving permission, rather than obligation.

Sense vs reference dependence(1)

You can’t understand what it is for somebody to be saying (and therefore thinking something) apart from the way they’re treated by some community. That’s a sense dependence: you can’t understand the one without the other.

It doesn’t follow that somebody who could do all of this wouldn’t have thoughts until/unless they were treated as having them; that would be reference dependence.

So just as an unconnected example, illustrating that distinction: suppose I defined ‘beautiful’ as “would cause pleasure in someone”. Now, then I’ve instituted a sense dependence between beauty and that sense and pleasure; if you can’t understand the concept of pleasure, you can’t understand the concept of beauty, which is a response dependent dependently defined consequence of it.

But now we ask, would there still be beauty if there were no pleasure? Were there beautiful sunset sunsets before there were any people to feel pleasure? That would be the reference dependence question. We say sure because they would have caused pleasure (if there were anyone there to feel it). And we can say, in a possible world in which there never were humans, it still could be that if there were, they would have responded to the sunsets with pleasure.

So, we could say there’s a sense dependence between these concepts, but there doesn’t need to be a reference dependence between doesn’t mean you can’t have the one without having the other it just means you can’t understand what one of them is without understanding the other.

So the claim would be that’s the relation between the thoughts and our normative attitudes are social attitudes. It’s not that the thoughts pop into existence at that point for them.

Romantic Views of Language(1)

People with romantic views of language: Derrida and Nietzsche. These are compatible with Wittgenstein believing language has no downtown.

Sellars disagrees: the language-language inferential transitions are of the first importance among those because what makes the entries and exits language entries and exits is the way they connect to the inferential moves. And so he would say to Derrida, “yes, we do all of these other wonderful things with the language, but that’s all parasitic on the meanings that things are given because of the role they play in the space of reasons... now, once you’ve got that up and running, once you’ve got those meanings to work with, now you can start to do other playful things with it, e.g. use them metaphorically. All sorts of things become possible. But that’s in principle a superstructure on this structure."

Transition(1)

Sellars story of how ‘the light dawns slowly over the whole’.

Both the infant and Koko the gorilla can be trained into a language (in the form of conforming to ought-to-be’s). At some point the human makes a jump - they have the concept and can be a trainer of others. What’s the nature of that jump?

For Sellars, this is a change in normative status, not a lightbulb that went off in one’s head. Like the change on your 21st birthday, when suddenly doing the very same thing, making the same pen scratches that you could have made the day before, would not be obliging yourself to pay the bank a certain amount of money every every month for the next 30 years. But after your 21st birthday, when you scratch your pen in exactly the same (physically descriptively, matter-of-factually) way, all of a sudden it has a hugely different normative significance because now you will be held responsible. You’ll be taken to have undertaken commitment in a way in which you were not eligible to undertake that commitment by doing the very same thing descriptively, the day before.

When you get good enough at the language game moves, you do get acknowledged by the community. We don’t characterize this physically-descriptively because we’re not describing someone / some matter-of-factual boundary that has been crossed. We’re not describing the child, we’re placing the child in the space of reasons.

It’s the difference between the one and a half year old, who toddles in to the living room. And as her first full sentence says, “Daddy, the house is on fire." Well, one doesn’t think that she has claimed that the house is on fire. She’s managed to put these words together, this is good. If the four year old comes into the living room and says “Daddy, the house was on fire", you hold her responsible, you say “how do you know? Did you smell smoke? And you know, what should we be doing? What follows if the house is on fire? What should we be doing?" You take her to have claimed this to have undertaken a commitment and you hold her responsible for it. The difference is not some light that’s going on. It’s a difference in normative status, ultimately a difference in social status.

This is the difference between just conforming to the pattern, and actually making claims. The radically anti-Cartesian aspect of Sellars is that this is also the the difference between conforming to the pattern and having thoughts at all.

However, as Dennett points out: you can treat any even inanimate object as an intentional system, e.g. this table as having the one desire that remain at the center of the universe. And the one belief that it is currently at the center of the universe, which is why it resists us moving it. (by extension, we treat our cats and dogs this way). So we should only treat things as thinking if we have to. Brandom takes an opposite view, that you should always treat something as talking if you can (note this is a very high bar).

The period prior to the child’s mastery and social status as a language speaker has some peculiarities. His verbal behavior would express his thoughts but, to put it paradoxically, the child could not express them. The child isn’t in a position to intentionally say that things are thus-and-so, even though it is in a position to say that things are thus-and-so. So there’s a question: which comes first, speaker’s meaning or semantic meaning?

Semantic meaning is a matter of what the words mean. No agent involved in that. In English, the word ‘molybdenum’ means the noble metal with 42 protons. Contrast with “When Humpty Dumpty says ‘glory’, he means a nice knockdown, drag-out fight”. Grice says speaker meaning comes first. Sellars says that is a Cartesian way of thinking about things, that the primary meaning is what words mean in the language process.

If I claim the notebook is made out of copper, I have (whether I know it or not), committed it to melting at 1084 oC and that it conducts electricity. My words mean those things, whether or not I mean to.

The kid produces vocal (not yet verbal) noises until he is a member of the language community (his verbal noises conform to enough ought-to-be’s).

As soon as he can say something, that’s the expression of a thought. To take him to be saying is to be taking him to be thinking out loud. It’s a further stage, when he can take expressing that thought as the object of an intention, and intentionally do as an action that say, before that, that’s just an act, it’s a performance, he can reliably produce appropriately, but not yet intentionally produce. An adult could be in this situation: Auction example. That’s the sort of position that the kid (who’s just crossed the line into being able to say something) is: she can produce a vocalization that will hold her responsible for, and which, accordingly, we take to express a thought. But she doesn’t yet have the concept. So, she can have the concept of its being red or the house being on fire. But not yet, the concept of endorsing something, or of making a claim that he’s saying can be a later development. And you need that concept in order to intend to be making a claim.

Important to make distinctions between different types of saying:

mere utterance (position of 1 year old)

saying that things are thus-and-so

having mastered the entries/exits/language-language moves, but no metalinguistic concepts

Could be called “merely thinking out loud”

Can perform speech acts.

Can express that something is read or even a desire for something (“I’m taking that’)

intentionally saying (telling someone) that things are thus-and-so

need concepts of asserting/believing as well as concepts of thus-and-so

Can perform speech actions.

Self consciousness.

We need to think of the child as being able to give evidence without the concept of evidence. This is important in the story of how the language game gets off the ground with the early hominids. But we have real experience with this: when teaching logic, it’s helpful to teach students to have the practical mastery of writing proofs (prior to them having the concept of a proof). They first get familiar with the symbol pushing game. (proof is a strong form of evidence). This is very common in mathematics education.

Lecture: Counterfactuals and Kant Sellars Thesis(13)

This lecture was delivered on September 23, 2009.

It concerns [13] and has two parts:

Part 1: Counterfactuals and dispositions.

Part 2: Causal modalities. (the focus of this lecture).

Counterfactuals and dispositions(1)

Uses Principia Mathematica notation which takes some time to learn.

Goodman has let the formalism of classical extensional logic mislead him in thinking about counterfactuals. He thought we could build up to counterfactuals from extensional logical vocabulary. The kind that can be built up by extensional logical vocabulary Sellars calls subjunctive identicals.

Goodman is impressed in Fact fiction and Forecast, with the difference between the claim ‘All copper melts at 1084 oC’ and ‘all the coins in my pocket are copper’. The first supports counterfactual reasoning (“if this coin in my pocket were copper, it’d melt at 1084 oC") whereas if this nickel coin were in my pocket, it wouldn’t be made of copper. However we can do some limited form of counterfactual reasoning: “if I pulled a coin out of my pocket, it would be copper”. We can always rephrase such counterfactuals (accidental generalizations) as a statement about something identical to an actual object. (The distinction is less sharp between genuine counterfactuals and subjunctive identicals is less sharp than he thinks, according to Brandom)

Makes distinction.

Defines a disposition.

Subjunctive vs counterfactual sentences(1)

Subjunctive conditional: if \(X\) were \(\psi\)’d, it would \(\phi\).

(example?)

Counterfactual conditional: if \(X\) had been \(\psi\)’d, it would have \(\phi\)’d.

These are both counterfactuals but very different:

If Oswalt didn’t shoot Kennedy, then some one else did.

If Oswalt didn’t shoot Kennedy, then someone else would have.

Linked by

Dispositions(1)

A kind term

More than a mere predicate: in addition to criteria of application, also have criteria of identity and individuation.

Two flavors: proper individuating terms as well as mass terms (which requires something like ’cup of’ to individuate)

Condition term

Intervention term

Result term

Canonical example: “If you put the sugar in water, it will dissolve.”

Distinct from a capacity claim: “Sugar has the capacity to dissolve" is a claim that there exists a condition and intervention such that the result obtain.

Linked by

Causal modalities(1)

Sellars first big idea: what was needed was a functional theory of concepts (especially alethic/normative modalities), which would make their role in reasoning, rather than their supposed origin and experience their primary feature. Sellars takes modal expressions to be inference licenses.

Jerry Fodor’s theory of semantic content in terms of nomological locking: can’t directly say anything about modality directly. Not alone: Dretske and other teleosemantic literature. Sellars wants to argue this program will never work.

An axial idea of Kant: the framework that makes description possible has features which we can express with words (words whose job is not to describe6 anything, but rather to make explicit features of the framework within which we can describe things).

The framework is often characterized with laws. With alethic modal vocabulary on the object side, normative vocabulary on the subject side.